Imagine waking up to find a massive lake where your farm used to be. That’s exactly what happened to farmers in California’s San Joaquin Valley in 2023 when Tulare Lake suddenly came back to life. After disappearing in the 1890s, this “ghost lake” returned with a splash, swallowing up farmland and surprising everyone.

Known as “Pa’ashi” (meaning “big water”) by the indigenous Tachi Yokut tribe, the lake’s return has brought both trouble and healing. While farmers scrambled to save crops and homes, native birds soared back as if they’d been searching for their lost home all along. Isn’t it amazing how nature finds a way to reclaim what once was hers?

The Historic Giant: California’s Forgotten Waterway

Picture a lake so big you couldn’t see across it. This massive inland sea stretched over 100 miles long and 30 miles wide at its peak, covering about 800 square miles of California’s Central Valley. Fed by snowmelt from the nearby Sierra Nevada mountains, the lake created a thriving ecosystem in what is now some of the driest farmland in America.

Fresno was once a lakeside town. One early visitor reported “driftwood piled in the trees of downtown Fresno” after flooding. The lake supported incredible wildlife diversity, too. Flocks of birds were so thick that when startled, they “lifted off like a giant clap.” Fish and frogs were everywhere.

For thousands of years, the Tachi Yokut tribe built their lives around Pa’ashi. They developed fishing techniques, boat designs, and celebrations that fit perfectly with the rhythms of the lake. You know, people and nature working together instead of fighting each other.

How Tulare Lake Vanished from California’s Landscape

The trouble started in the 1850s when California began converting what they called “public lands” into private farms. Of course, these weren’t really “public” at all but had been indigenous territories for centuries. This land grab changed everything.

Between the 1850s and 1890s, farmers and developers got busy. They built dams, levees, and irrigation canals that diverted the four rivers feeding the lake basin. By 1920, the lake was mostly gone, replaced by fields of cotton, almonds, and other crops. A vast wetland ecosystem became farmland practically overnight.

The lake tried to make comebacks during super-wet years. It popped up briefly in the 1930s, 1969, 1983, and 1997. Each time, though, pumps and canals quickly drained the water away. People weren’t ready to give up valuable cropland for an old lake.

Read More: Scientists Report Rare Ice Growth in Antarctica After Years of Steady Decline

The Surprising 2023 Comeback of Tulare Lake

The winter of 2022-2023 brought rain like nobody had seen in ages. California got hit by a series of powerful storms called “atmospheric rivers“ that dumped tons of water. These weren’t your average rainstorms. They filled reservoirs, caused flooding, and buried the mountains in snow. When spring came, all that snow started melting. The water rushed down the mountains and overwhelmed all the canals and pumps meant to keep the lake bed dry. Nature said, “Remember me?”

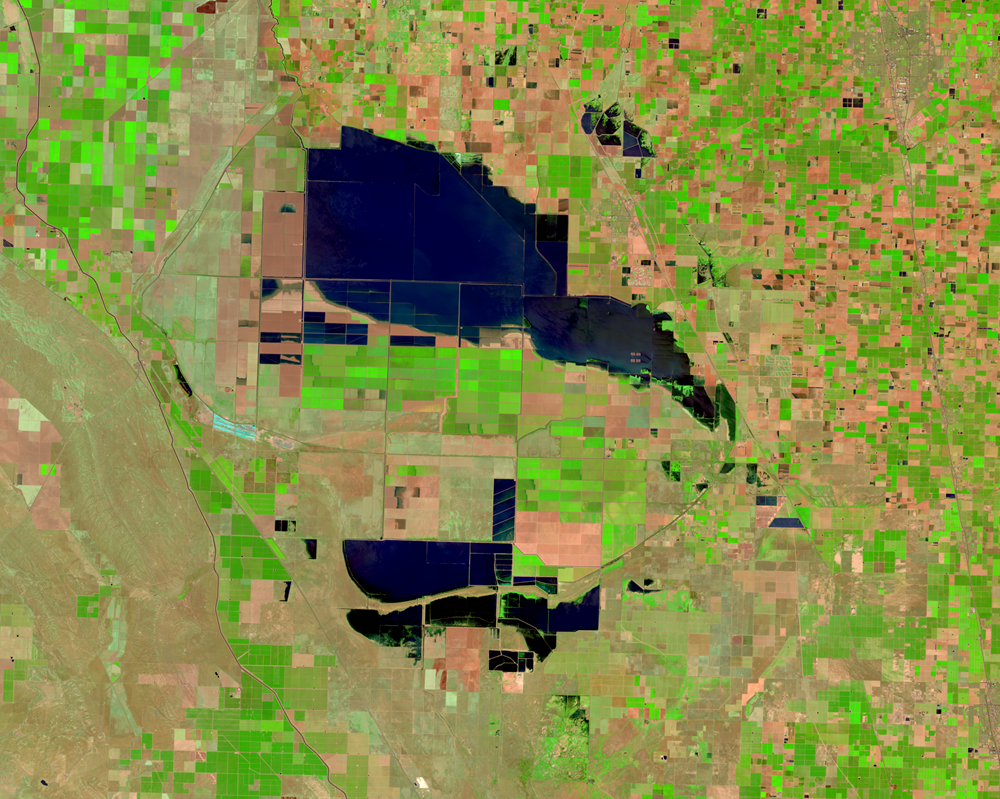

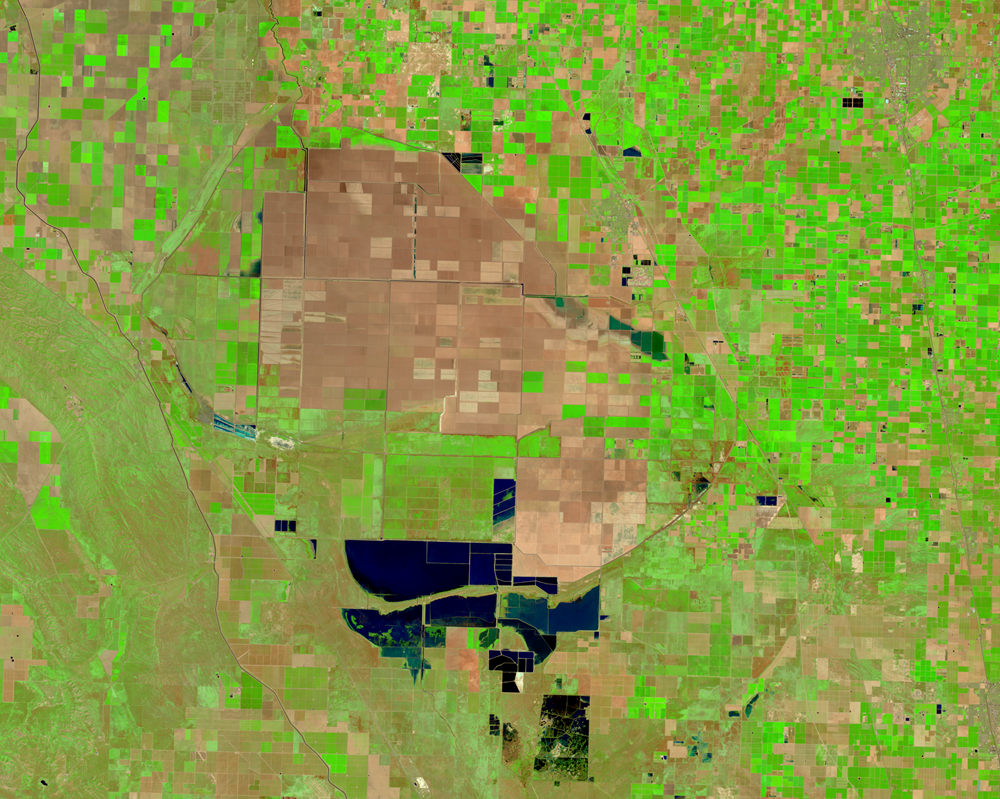

By April 2023, the reborn lake covered 120,000 acres, about 180 square miles. At its highest point, it flooded more than 10% of Kings County! Hundreds of farm buildings and homes went underwater. Satellites tracked the whole thing, showing dark blue water spreading across the tan and green patchwork of farms.

By March 2024, the lake had shrunk to around 4,500 acres. But some water experts think it could grow again if more storms come. Mother Nature can be pretty stubborn when she wants to be.

Winners and Losers: The Impact of The Lake’s Return

Tulare Lake’s return created a weird mix of good and bad news. For wildlife, it was like hitting the jackpot. Pelicans, hawks, ducks, and owls showed up almost immediately. How did they know? As one researcher put it, “Something that continues to amaze me is that the birds know how to find the lake again. It’s like they’re always looking for it.”

For the Tachi Yokut tribe, Pa’ashi’s return felt like healing old wounds. “As Native people, there has been something missing in our spirit,” explained Robert Jeff, the tribe’s vice chairman. “What you see behind us now is Pa’ashi has reawakened. At the same time, it’s reawakened a lot of spirits.” Farmers, though, had a rough time. They lost over $300 million in Kings County alone. About 60,000 cows needed new homes fast. Crops like tomatoes, cotton, and pistachios were flooded out. Farm equipment worth millions sat underwater.

But there was an unexpected bonus. The returning waters added about 3.8 million acre-feet to underground aquifers. In a region where people have been pumping out too much groundwater for years, this natural refill helps everyone in the long run.

The Future of Tulare Lake: Finding Balance

As the waters start to shrink again, people are arguing about what should happen next. Many farmers want their land back ASAP. They’ve spent a lot of money on pumps to move water out of the basin. But wait a minute. Scientists, conservation groups, and the Tachi Yokut tribe see things differently. What if we kept parts of the lake around permanently? This could help control floods naturally, store water for dry times, and give wildlife a home while still letting farming happen in other areas.

With climate change making California’s weather more extreme, this talk matters now more than ever. The state swings between terrible droughts and massive floods these days. Perhaps this ancient body of water has something to teach us about dealing with these swings? Leo Sisco, a Tachi Yokut Tribe member, feels proud that his generation gets to see the lake return. “It makes me swell with pride to know that, in this lifetime, I get to experience it,” he said. His tribe wants to “work together with farmers, local people, and the government” to find solutions that work for everyone.

In simple words, as tribal vice chairman Jeff put it: “The land needs that lake.” And maybe we need Tulare Lake too, as both a reminder of our past and a guide for our future.