On the far south-eastern edge of Western Australia, a group of partners is planning to build something massive: the Western Green Energy Hub (WGEH). Picture a huge clean-energy estate on the world’s largest single exposure of limestone bedrock, called the Nullarbor. There, the constant wind and hot sun are harnessed to create “green” hydrogen and ammonia, which will then be used for heavy industry and shipping. If everything goes as planned, the WGEH will produce approximately 70 gigawatts of combined solar and wind. To put it into perspective, that’s more capacity than many countries’ entire power systems. Let’s find out how WGEH differs from other climate change initiatives and large-scale solar projects.

The Western Green Energy Hub

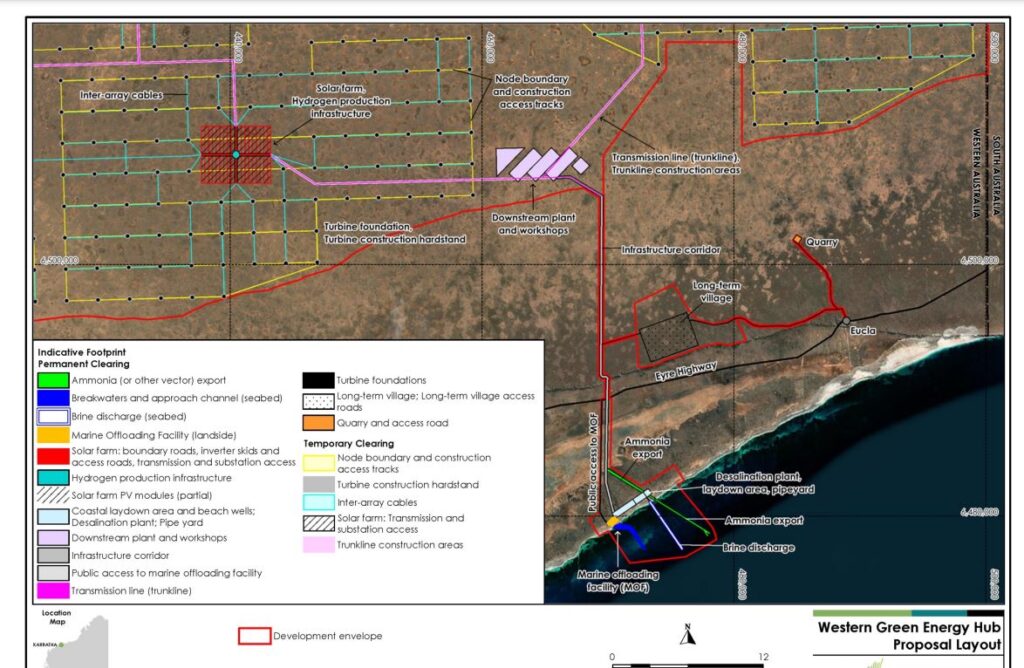

The plan is to build the WGEH near the town of Norseman, a massive area that stretches towards the coast. The Western Green Energy Hub will consist of thousands of large solar farms and wind turbines. The electricity produced by these solar and wind sources will then power electrolysers, which are specialized machines that split water into oxygen and hydrogen. The hydrogen can then either be turned into green ammonia or used directly. The developers say that the site could potentially produce around 5.4 million tonnes of green hydrogen annually at full scale.

The three partners involved in the project are InterContinental Energy, CWP Global, and Mirning Green Energy Limited (MGEL). Both InterContinental Energy and CWP Global are international renewable energy developers with extensive experience in large-scale solar projects. Mirning Green Energy Limited is owned by the Mirning Traditional Lands Aboriginal Corporation, which makes the traditional owners of the land part owners of the project.

The project still only exists on paper, though, and no construction on the project has begun yet. At the moment, the developers are still working through various studies, engaging with the community, and getting the necessary state and federal approvals. So far, their plan is to build the hub in different stages, with the first stage being much smaller than the final version. If everything goes to plan, they hope to have their final investment decision (FID) around 2029 for the first phase. Then, over the following years, the project would scale up.

Indigenous and Environmental Concerns

The biggest issue with the intended location of the Western Green Energy Hub is that it isn’t some barren landscape. Known for its limestone bedrock, the landscape also contains underground waterways and expansive cave networks, and its delicate ecosystems are home to some unique local species. According to various conservation groups and scientists, and building of roads or foundations could seriously disturb both surface and underground habitats. Therefore, the WGEH project has to be subjected to very detailed environmental assessments.

There will likely be certain exclusion zones, where nothing will be allowed to be built. There will also need to be strict regulations regarding water usage and ongoing monitoring. Then there is the issue of the indigenous owners of the land. Since the proposed project falls on the land of the Mirning people, the developers have promised not to do anything without the consent of the community. Large-scale projects such as this one also typically face many big challenges. For one, the required environmental reviews usually take time, especially when it comes to sensitive landscapes.

Then there are the various cultural heritage processes, which can take years before any actual construction begins. Additionally, the site is quite remote, which brings its own logistical considerations and issues. Trying to build, transport, and maintain thousands of turbines, solar fields, and pipelines would require considerable coordinating efforts. There is also plenty of international competition in places such as the United States and the Middle East.

What Would the Benefits of the WGEH Be?

Well, first, there is the potential environmental impact. Replacing fossil-based hydrogen and ammonia would cut a considerable chunk of industrial emissions. Supplying clean fuels for ships or steel could help decarbonize various sectors that are usually hard to change. Additionally, a working model where traditional land owners have a seat on the board, equity, and consent rights could set a precedent when it comes to how big projects are carried out on indigenous land. However, at the moment, it’s a long game, with much planning still left to do and approvals to acquire.

For now, they are aiming for an initial investment decision towards the end of this decade. The WGEH could become a highly-regarded blueprint for future green energy and climate change initiatives. However, in order to do that, they will need to show that they can protect the environment and keep the Mirning community consent at the heart of the project. They cannot damage the delicate ecosystems that scientists are still learning more about all the time. In fact, in a recent survey of one cave, researchers documented thousands of unknown specimens.

Read More: Grazing Sheep Beneath Solar Panels Show Surprising Changes That May Transform Farming