As humans, we care very much about the imaginary borders we’ve created between countries. Animals, of course, do not. Their movement patterns and ways of life are not dictated by international politics, but rather instincts, weather, and food availability. Vultures, however, appear to be avoiding one particular border: Portugal.

These scavenger birds are clearly not avoiding the Potugese border for political reasons, so what is going on? The story of the Iberian vultures is an example of how policy decisions can change wildlife behaviour.

Why Are Vultures Avoiding Portugal?

Spain is home to 90 percent of all the scavenging birds of prey in Europe. Their main source of food is carrion- the decaying flesh of dead animals. These birds will fly between three hundred and four hundred kilometers per day to find a carrion meal.

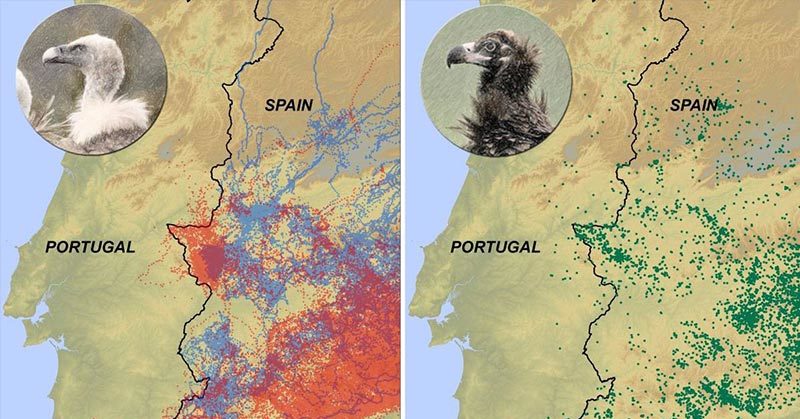

Of course, vultures do not care about country lines in their search for food. That being said, over the last several years the birds have been avoiding the Portugese border as if they were aware that it was a separate country [1].

Researchers from both Spain and Portugal tagged 71 vultures and tracked them for three years. During this time, only thirteen of those birds ever ventured into Portugal. Why? According to their study, it has to do with the availability of carcasses [2].

In 2001, the European Union mandated that farmers immediately bury or incinerate dead cattle. They made this law in order to curb the spread of mad cow disease. In 2011, however, the EU changed regulations to allow countries to decide for themselves if they should leave the carcasses out in the open or not.

Given their massive vulture (and other carrion bird) population, Spain decided to lift the 2001 mandate. In Portugal, however, the rule is still in place. This means that there is plenty of food for the vultures in Spain, and virtually none in Portugal. Thus, the birds have no reason to go there [3].

The researchers pointed out that since there are no major differences in climate or geography on either side of the border, the availability of carcasses is the primary reason for the abrupt decline in vultures crossing into Portugal.

Read: Mushrooms Can Eat Plastic, Petroleum and CO2

Species Pay the Price of Carrion Ban

Eneko Arrondo is a doctoral student at the Doñana Biological Station (EBD-CSIC) and the main author of the study. He explains that the measures the EU took to contain mad cow disease were very drastic. The ban on carrion affected the Iberian Peninsula significantly, since it is an international reservoir for carrion birds because it took away their food source.

He and several others worked hard to have the mandate changed to protect the livelihoods of these animals.

“Thanks to scientific work and the involvement of many managers in Spain, it was found that [European legislation] had a very negative environmental impact. So much data was put on the table that Europe understood,” he said [1].

In 2011, a Royal Decree in Spain allowed for the storage of animal carcasses in certain areas. Portugal, however, never changed its policy. Nicolás López is the head of threatened species at SEO / BirdLife.

“Now there is the paradox that there is a different regulation within the Iberian Peninsula in each country,” he says, “and threatened species pay the price for administrative borders.” [1]

According to the study authors, international integration of sanitary policies is necessary for the conservation of animals like vultures, who travel hundreds of kilometers in a day. Arrondo says that this will be very important for the recovery of vulture populations in Portugal.

How To Fix the Carrion Shortage

Joaquim Teodósio is a spokesman for the Portuguese conservation NGO SPEA, a subsidiary of BirdLife International. His organization is working with the General Directorate of Food and Veterinary Medicine (DGAV) and the Institute of Forest and Nature Conservation (ICNF, for its acronym in Portuguese).

Together, they are working to solve the carrion shortage in Portugal. One of their proposals is to implement closed areas where farmers can leave carcasses. Another is to give permits to farmers so they can leave carrion in authorized fields.

Not only would this be beneficial for the vultures, it would also take away the large financial burden of collecting dead animals, transporting them, and disposing of them [1].

The plight of the Portugese vultures is an example of how a political border can become an ecological one if countries and regions don’t work together to create policies that protect wildlife.

Keep Reading: The Coconut Crab Kills Birds And Breaks Bones – And May Have Eaten Amelia Earhart Alive