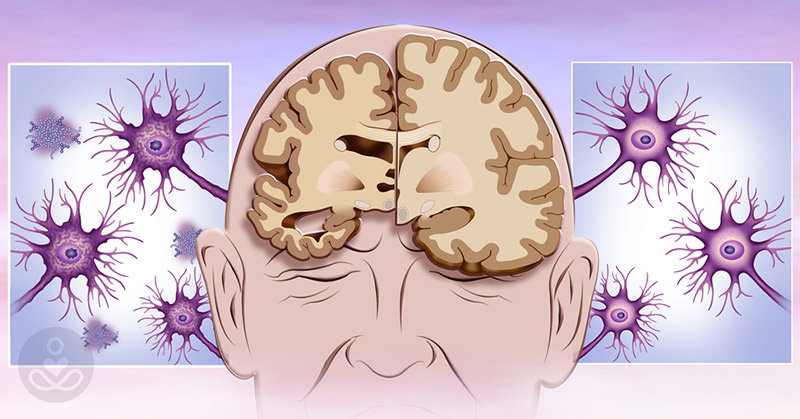

What is Dementia?

The World Health Organizing defines dementia as “a syndrome—usually of a chronic or progressive nature—in which there is a deterioration in cognitive function (i.e. the ability toprocess thought) beyond what might be expected of normal aging. It affects memory, thinking,orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capacity, language, and judgment.” (1)

It isn’t strange that most of us think of Alzheimer’s first when we hear the word dementia. It is, after all, the most prevalent of the cognitive illnesses associated with dementia. It’s also notsurprising that most people have a personal connection with a friend or family member suffering from a cognitive illness since there are 50 million internationally documented cases and approximately 10 million new cases diagnosed each year. (1)

Be Proactive

We live in a society where most people are reactive to health problems rather than proactive. A crisis of body reminds us of our limited time on this spinning rock and our mortality—conscious action can kick into gear when faced with these crises. Fortunately, our most precious commodity—our brain—is encased in a tough exterior to protect it from the physical traumas that can change the course of our lives forever.

Unfortunately, physical trauma is not the only factor that can damage our brains. In addition to the unavoidable circumstances, such as genetics, age, and sex, there are a slew of factors that we can take control of immediately. While people often associate a certain amount of forgetfulness to aging, a deteriorating mind to the point of developing a form of dementia is not a natural progression of life. It’s important to be aware of all that we can control regardless of age.

The Hearing Loss Connection

Does it sound ludicrous? How could there possibly be a connection between hearing loss and dementia?

Shockingly, articles dating back to the 1980s link hearing loss (HL) and dementia, prevalently in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). In a 1989 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), a control group without dementia and one with dementia—100 people in each group, all similar in age, sex, and education—were used to determine whether hearing impairment correlated to cognitive dysfunction. The study showed “an association between hearing impairment and dementia” and supported “the hypothesis that hearing impairment contributes to cognitive dysfunction in older adults.” (2)

Another study published in 2014 tracked 4,463 subjects aged 65 and older, all without dementia and 836 of which had hearing loss. Of those subjects, 16.3% with HL developed dementia as opposed to 12.1% without HL. The results “showed HL was associated with a faster decline…than those without HL.” (6)

A recurring possibility of why this connection exists is the social implication. With hearing loss comes a certain amount of isolation and withdrawal from situations one might not have previously avoided. This departure from socializing can lead to behavioural changes, such as depression, and eventually this can have brain-altering effects. One study suggests that “hearing loss leads to cognitive decline because of degradation of inputs to the brain.” (3)(4)

Other Risk Factors for Dementia

According to a review article published in The Journal of the Formosa Medical Association (2009), the following are factors contributing to dementia: (5)

- Genetic Effects

- Age

- Sex

- Physical Activity

- Smoking

- Drugs

- Education

- Alcohol Consumption

- Comorbidity (two or more diseases presenting in an individual simultaneously)

- Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Environment Factors (these focused on nutritional factors in the article)

While there are numerous factors involved with the onset of dementia, holistically it is impossible to ignore lifestyle as one of the influential factors. Studies show that factors such as diabetes, smoking, and hypertension are associated with HL.

As long as there is breath in our lungs, we have the ability to make better choices for our longterm health. Most often, the plight of youth is not realizing that “one day” is actually nearly upon us, and the simplest (albeit not always the easiest) way to be proactive in an attempt to stave off cognitive as well as other illnesses is to make nutritionally sound decisions and stay active.

Because there’s a link between hearing loss and dementia, the logical delineation would be to assess what other factors exist in our lives that could lead to hearing loss in order to minimize long term effects. For example, diabetes mellitus (DM) has been known to cause hearing loss. One study sites that “DM is closely linked to hearing damage. Both large and microscopic-size blood vessels are affected in DM.” When blood vessels are affected, nerve damage can occur. “When such pathological changes involve the cochlea and auditory nerve, cochlear and/or neural hearing loss follows.” (7)

Even those with the genetic predisposition to developing late onset AD—the presence of the APOE-e4 gene (8)—can benefit from certain nutritional practices. The MIND (Mediterranean- DASH-Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) diet was created by Rush University in an attempt to address the benefits from both diets (Mediterranean and DASH—Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension), while also incorporating specific foods that have nutritional benefits to brain function and cognition. There is an emphasis on eating leafy greens (antioxidant vitamin E and folate), berries (polyphenols), and seafood (omega 3 fatty acids), as well as other vegetables, olive oil, wine, nuts, whole grains, and poultry. (9) The diet also focuses on eliminating refined and sugary foods, as well as limiting red meats, butter and margarine (although a small amount of butter is allowed), and cheese. Their data suggested that “even loosely adhering to the MIND diet may help to delay occurrence of AD.” (9)

Conclusion

Dementia has long eluded the scientific community. There are theories and hypotheses, and they are coming ever-closer to breakthroughs. The brain is such an intricately woven entity that the fullest extent of possibilities has yet to be exhausted.

Sources

- World Health Organization. (2018). Dementia. [online] Available at: https://www.who.int/newsroom/

fact-sheets/detail/dementia [Accessed 17 Jul. 2018]. - Uhlmann RF, Larson EB, Rees TS, Koepsell TD, Duckert LG. Relationship of Hearing

Impairment to Dementia and Cognitive Dysfunction in Older Adults. JAMA. 1989;261(13):

1916–1919. doi:10.1001/jama.1989.03420130084028 - Anon, (2018). [online] Available at: Https://www.webmd.com/Alzheimer’s/news/20180530/

risk-factors-that-put-you-on-the-road-to-dementia [Accessed 17 Jul. 2018]. - Lin, F., Metter, E., O’Brien, R., Resnick, S., Zonderman, A. and Ferrucci, L. (2011). Hearing

Loss and Incident Dementia. Archives of Neurology, 68(2). - Chen, J., Lin, K. and Chen, Y. (2009). Risk Factors for Dementia. Journal of the Formosan

Medical Association, 108(10), pp.754-764. - Gurgel, R., Ward, P., Schwartz, S., Norton, M., Foster, N. and Tschanz, J. (2014).

Relationship of Hearing Loss and Dementia. Otology & Neurotology, 35(5), pp.775-781. - Xipeng, L., Ruiyu, L., Meng, L., Yanzhuo, Z., Kaosan, G. and Liping, W. (2013). Effects of

Diabetes on Hearing and Cochlear Structures. Journal of Otology, 8(2), pp.82-87. - 1. Reference G. APOE gene. Genetics Home Reference. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/

APOE#conditions. Published 2018. Accessed July 20, 2018. - 2. Morris M. Nutrition and risk of dementia: overview and methodological issues. Ann N Y

Acad Sci. 2016;1367(1):31-37. doi:10.1111/nyas.13047