This article was originally published in August 2019 and has since been updated.

Colon cancer is the third most common cause of death in the world, and in the United States, it’s the second leading cause of cancer deaths [1].

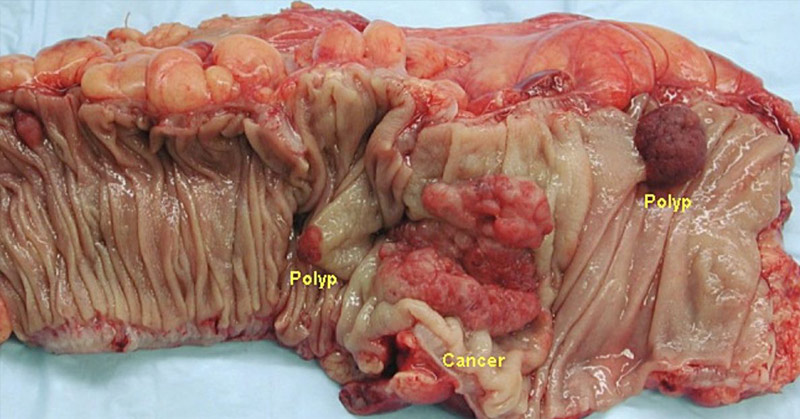

Colon cancer, if it’s not obvious, is cancer of the colon, which is also known as the large intestine. Located at the end of the digestive tract, the colon is partially responsible for removing fluids and nutrients from food, before moving solid waste to the rectum.

Although it’s sometimes referred to as colorectal cancer, colorectal cancer actually refers to cancers of both the colon and the rectum [2]. To break down the cases, about 71 percent of colorectal cancers are in the colon while 29 percent are in the rectum [1].

Although, like many cancers, there are different factors that influence its growth, we’ll be focusing on the role of the gut microbiome (the bacteria in your gut) and fiber (including resistant starches) in colon cancer.

The Role of Gut Bacteria in Colon Cancer

Researchers admit that “we currently have only a very primitive understanding of the microbiome and how it functions in the human body”, meaning we still have yet to understand the magnitude of gut bacteria in our overall health [3].

What we do know is that good bacteria in our gut take some of the fiber we eat to make short chain fatty acids (one of which is butyrate) that protect us from cancer. There’s research documenting butyrate’s role in preventing colon cancer and also its role in getting rid of cancer [4].

When colon cancer cells are exposed to butyrate, it actually stops cancer growth. Butyrate is formed in the colon from the fermentation of carbohydrates, particularly resistant starch [5].

Resistant starch is a type of low-viscous fiber and is important for colon health and can even help reduce your risk of colon cancer [6].

There’s also evidence showing the importance of fiber for survivors of colon cancer; even adding as few as five additional grams per day had a significant impact on colon health [7].

But what about other populations such as those in West Africa where people don’t eat a lot of traditional fiber, yet still have low rates of colon cancer? Research on these populations have shown that their colons are still producing beneficial short chain fatty acids, primarily from resistant starch consumption [8].

What Are Resistant Starches?

Resistant starch is any starch that is not digested and absorbed in the upper digestive tract (the small intestine) and so passes into our colon to feed good bacteria. It’s technically a type of dietary fiber and can be found in bananas, potatoes, grains, and legumes [9]. It can often depend on how ripe or cooked the fruit or vegetable is. For instance green/unripe bananas contain higher amounts of resistant starch.

There is research documenting the potential for starch to protect against colon cancer [10].

In a typical diet, about 10 percent of starch doesn’t get digested and is called resistant starch. Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced during fermentation reduce the pH of the colon, helping to regulate luminal (space within the colon) pH. In turn, adequate resistant starches and other fibers can help produce SCFAs and affect the composition of the microbiome. In vitro and animal studies have shown that this change in microbiota can actually protect against pH sensitive pathogenic bacteria [26].

Research shows fermentation is a “key factor” in enhancing the protective effect of fiber on colon cancer. In this research, eating resistant starch was another way of stimulating fermentation [11].

Some research also suggests that eating resistant starch can help offset the negative impact of daily meat eating on the colon [12].

We can get resistant starch from eating foods such as oats, legumes (beans), and green bananas and plantains, in addition to “cooled” cooked/parboiled starches, including rice and potatoes. You can even reheat them once they’ve cooled, as the resistant starch has been shown to stay in tact [27].

Raw potato starch is also very high in resistant starch, and feeds good bacteria that may help protect the colon against cancer.

Carbohydrates can ferment in the colon and also product butyrate (a type of SCFA), although only a small fraction of undigested carbs actually make it to our colon, but it may induce protective effects similarly to a high fiber diet [13].

Resistant starches have also been shown to help support a healthy weight, a healthy heart, improve blood sugar, and of course, digestive health [14].

There are currently no formal guidelines for how much resistant starch one should eat, but some suggest eating 15 grams or more a day for health benefits (this is not to be confused with total fiber consumption, which should total around 30 grams, as we’ll see later).

How Does Meat Consumption Influence Colon Cancer Risk?

So we’ve talked about fiber, good bacteria, and resistant starch when it comes to colon cancer health. Now it’s time to address the elephant in the room, and one that’s been consistently linked to a higher risk of colon cancer: meat.

Red meat and processed meat has been shown to increase the risk of colorectal cancer by up to 30 percent [15]. Other research suggests this percentage could jump to 50 percent when meat consumption is high [16].

Other conclusions based on nine different studies found “strong evidence” that eating processed meat increases the risk of colorectal cancer by 18 percent per 50 grams of processed meat per day [17].

(How much is 50 grams of processed meat? It’s two and a half slices of bologna—see more amounts of different kinds of meat by scrolling through these photos!)

People who eat diets high in red and processed meat and low in fiber produce compounds in their colons called N-nitroso compounds. These compounds have suspected carcinogenic effects on the body and can influence DNA changes, potentially leading to cancer. Research shows that eating a diet high in fiber helps people who eat meat produce less of these compounds, although vegetarian diets showed the lowest amounts [18].

Research suggests consumption of fiber such as resistant starches can help offset the risk created by eating meat [19].

Foods You Can Eat to Protect Against Colon Cancer

So how much fiber should you get every day? You should aim for at least 20-35 grams [20].

You can eat the foods we discussed above including beans, oats, and plantains, but you should also eat plenty of fruits and vegetables, including dark leafy greens, seeds and nuts.

Should you avoid meat entirely? Research shows that poultry and fish don’t necessarily have the same effect on the colon as red meat, but eating any type of meat comes with its own risk thanks to mercury and microplastics in fish, and genetically engineered chicken [21], [24], [25].

I always advocate for eating meat only if you know exactly where it came from and what kind of life it lived—and, of course, not eating meat all the time. I only eat meat twice a week and it’s from a local ranch where I know how the animals were treated and what they ate.

Eating meat is a personal decision, but eating plants the majority of the time has been shown to have plenty of health benefits, even for the health of your gut microbiome [22].

So how else can you protect your colon?

In addition to eating lots of veggies, fruits, and fiber, you should exercise, maintain a healthy weight, and reduce alcohol and tobacco use. You can also get screened for colon cancer starting at age 45 and talk to your doctor to determine your risk and screening recommendations [23].

Although people don’t like to talk about colon cancer, awareness of this common condition could help people implement protective measures in place to avoid it—so don’t underestimate the importance of fiber, resistant starch, and a healthy gut bacteria to help protect against cancer!

Keep Reading: 8 of the Best Anti-Cancer Foods. It’s Time to Start Adding them to Your Diet

Sources

- “Colorectal Cancer.” CC Alliance

- “What is Colon Cancer?..” Colon Cancer Coalition

- “Probiotics in the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer.” NCBI. Robert Hendler and Yue Zhang. September 2018.

- “Butyrate and colorectal cancer: the role of butyrate transport.” NCBI. Pedro Gonçalves and Fátima Martel. November 2013.

- “Colorectal Carcinoma: Why Is There a Lower Incidence in Nigerians When Compared to Caucasians?.” NCBI. David Omoareghan Irabor. December 29, 2011.

- “Dietary fiber intake and risk of colorectal cancer and incident and recurrent adenoma in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial1,2.” NCBI. Andrew T Kunzmann, Helen G Coleman, Wen-Yi Huang, Cari M Kitahara, Marie M Cantwell, and Sonja I Berndt. August 12, 2015.

- “Fiber Intake and Survival After Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis.” JAMA Network. Mingyang Song, MD, ScD, et al. November 2, 2017.

- “Health effects of resistant starch.” Wiley. S. Lockyer and A. P. Nugent. January 5, 2017

- “Starch intake and colorectal cancer risk: an international comparison.” NCBI. A Cassidy , S A Bingham and J H Cummings. May 1994.

- “The role of carbohydrate fermentation in colon cancer prevention.” NCBI. I P Van Munster and F M Nagengast. 1993.

- “Carbs 101.” MD Anderson. Kellie Bramlet. July 2016.

- “WHAT IS RESISTANT STARCH?” Hopkins Diabetes Info.

- “Red Meat and Colorectal Cancer.” NCBI. Nuri Faruk Aykan. December 28, 2015.

- “Nominations to the National Toxicology Program (NTP) for the Report on.” Carcinogens, “Meat-Related Exposures” NTP. May 1, 2017.

- “Red meat and bowel cancer risk – how strong is the evidence?” WCRF. Rachel Thompson. October 23, 2015.

- “Red meat and colon cancer.” Harvard. January 1, 2008.

- “Fiber and colon cancer.” NCBI. L R Jacobs. December 1988.

- “Red meat, chicken, and fish consumption and risk of colorectal cancer.” NCBI. Dallas R English, et al. September 2004.

- “Plant-Based Diets Promote Healthy Gut Microbiome.” PCRM. April 23, 2019.

- “Six Ways to Lower Your Risk for Colorectal Cancer.” Cancer. ACS Medical Content and News Staff. February 5, 2025.

- “Microplastics increase mercury bioconcentration in gills and bioaccumulation in the liver, and cause oxidative stress and damage in Dicentrarchus labrax juveniles.” Nature. Luís Gabriel Antão Barboza, et al. October 23, 2018.

- “The Genetically Modified Chicken: How We Have Altered ‘Broiler’ Chickens for Profit.” One Green Planet. Kevin O’Connor and Mercy for Animals. 2020.

- “The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism.” NCBI. Gijs den Besten, et al. September 2013.

- “Effect of cooling of cooked white rice on resistant starch content and glycemic response.” NCBI. Steffi Sonia , Fiastuti Witjaksono and Rahmawati Ridwan. 2015.