In the world of philanthropy, funding sources often include grants, donations, or investments. But for Catherine Schweitzer, the executive director of the Baird Foundation in Buffalo, New York, a unique and steady income stream sets her organization apart: royalties from the sale of Listerine. Every year, the nonprofit earns approximately $120,000 in passive income from its 0.5% share in the Listerine royalty trust.

These payments arrive quarterly, stemming from Johnson & Johnson’s commitment to honor a contract penned over 140 years ago. “It’s stable, predictable cash on an annual basis,” Schweitzer said. “For a nonprofit like ours, it provides invaluable financial security.”

What makes this arrangement remarkable is that neither Schweitzer nor her foundation has any direct connection to the mouthwash or its manufacturing company. Instead, they are part of a long list of individuals and organizations that have inherited or acquired stakes in a peculiar legal agreement—a deal that continues to generate millions for its holders.

How a 19th-Century Contract Became a Goldmine

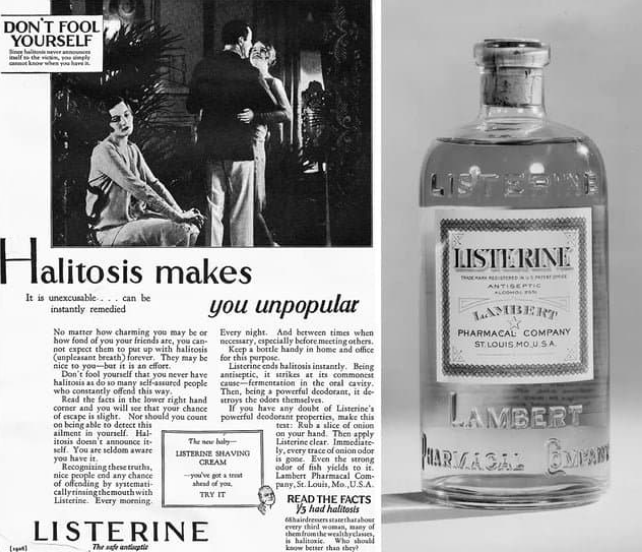

Listerine’s origin story begins with Joseph Joshua (J.J.) Lawrence, a Civil War doctor turned entrepreneur. Inspired by British scientist John Lister’s antiseptic techniques, Lawrence developed a formula for a disinfectant that could be used on wounds. However, his product didn’t achieve commercial success until a local pharmacist, Jordan Wheat Lambert, licensed it in 1881.

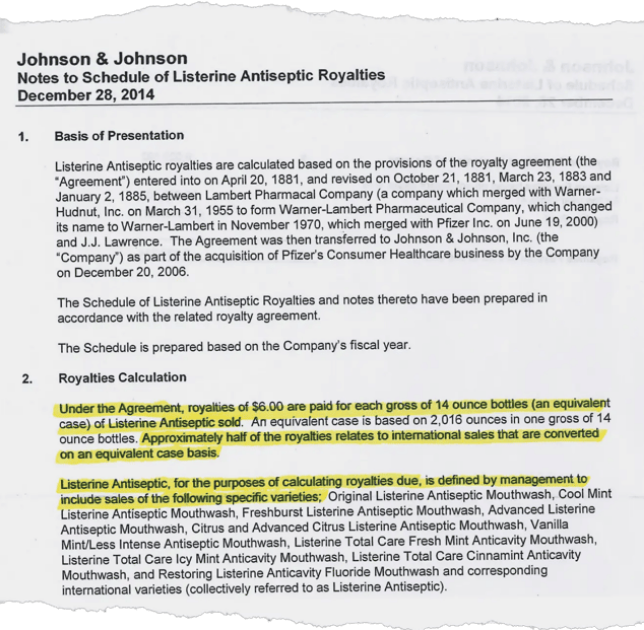

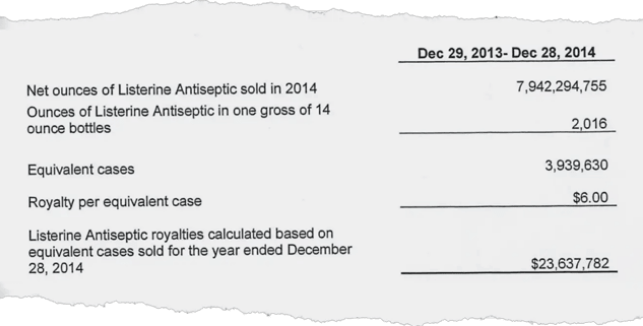

The contract was handwritten on the back of a medical publication owned by Lawrence. It stipulated that for every gross (144 bottles) of Listerine sold, $6 would go to Lawrence’s “heirs, executors, or assigns.” Neither man anticipated the product’s eventual commercial success, nor did they foresee the far-reaching implications of the contract’s lack of an end date.

By the early 20th century, Listerine had evolved into a household staple, thanks to innovative marketing by Lambert’s son, who rebranded the product as a mouthwash for fighting bad breath. Sales skyrocketed, and the royalties owed under the original agreement became a substantial fortune.

A Web of Unexpected Beneficiaries

Initially, J.J. Lawrence’s granddaughter, Vera, inherited the royalties. But over time, as family members sold off their shares, the trust fragmented. By the mid-20th century, portions of the royalty trust were acquired by institutions such as Wellesley College, the Salvation Army, and the Catholic Archdiocese of New York. Today, the beneficiaries of Listerine royalties include a mix of nonprofit organizations, universities, wealthy individuals, and even churches.

For instance:

- Fisk University, a historically Black college, earned $121,700 from Listerine royalties in 2016.

- Christ Church Oyster Bay, a Long Island parish, makes roughly $90,000 annually—about 10% of its revenue—from the royalties.

- The Boyce Thompson Institute has earned over $2.4 million since acquiring a stake in 1967.

From Private Auctions to Public Bidding

For much of the 20th century, Listerine royalty shares were traded privately, often through closed-door auctions among wealthy individuals or organizations. But in recent years, platforms like Royalty Exchange have brought these opportunities into the public eye. In 2020, a fractional share of the royalties was sold at auction for $561,000. Two years later, a larger stake fetched $1.795 million.

Financial analysts see this shift as part of a broader trend in alternative investments, with royalty trusts gaining popularity for their stability and unique appeal. “Royalties are becoming an increasingly attractive asset class,” said Melissa Tran, a financial analyst specializing in alternative investments. “For investors, owning a piece of history like Listerine is as much about pride as it is about returns.”

The Erosion of Value in Perpetual Royalties

Despite its enduring legacy, the value of the Listerine royalty trust has declined over time. Because the original contract set a flat payment of $6 per gross of bottles sold, the real value of these royalties has been steadily eroded by inflation. In today’s dollars, $6 in 1881 is worth about $172—a stark contrast to the booming sales figures Listerine now commands.

However, many beneficiaries, including Schweitzer, view the royalties as a valuable financial resource. “Even with inflation, it’s a remarkable windfall,” she said. “We’ve been able to reinvest this income into programs that make a difference in our community.”

A Legal Landmark with Timeless Lessons

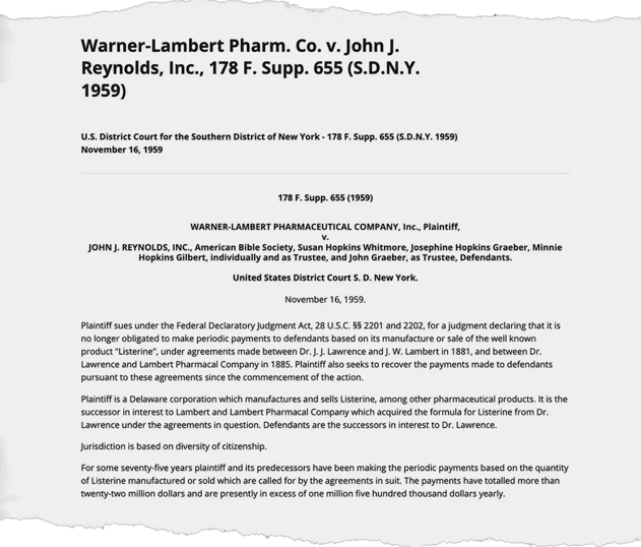

In 1959, Warner-Lambert (the predecessor to Johnson & Johnson) sought to terminate the royalty contract, arguing that the formula for Listerine had entered the public domain. The New York courts disagreed, ruling that the agreement’s perpetual nature was valid and enforceable.

“It’s a case that law students study to this day,” said Jorge L. Contreras, a law professor at the University of Utah. “It underscores the importance of careful drafting in contracts and the unforeseen consequences of perpetual agreements.”

A Unique Legacy in Modern Investing

The Listerine royalty trust remains a curious anomaly in the world of intellectual property and finance. For more than a century, this one-of-a-kind agreement has generated millions for its holders, all thanks to a handwritten contract that neither party thought would endure.

Today, as organizations and individuals continue to benefit from the royalties, the story of Listerine stands as a testament to the enduring power of legal agreements—and the unexpected ways they can shape history. “It’s a legacy we’re proud to be a part of,” Schweitzer reflected. “As unconventional as it may seem, this income allows us to do meaningful work. That’s what matters most.”

Read More: Alcohol-Based Mouthwash May Disrupt Oral Microbiome and Increase Risk for Certain Cancers