There is a secret forest in Southern Ontario, Canada, that has been hiding in plain sight. Growing on the cliffs of the Niagara escarpment, the trees’ precarious positioning has left them completely untouched by humans, despite being mere minutes away from bustling urban areas.

One ecologist found the ancient forest accidentally, and was so shocked he almost didn’t believe what he was seeing.

A Secret Forest

Doug Larson was working on the cliffs of the Niagara escarpment, not far from his home in Guelph, Ontario. He and his students were there studying the ecology of the cliff faces because they were relatively untouched by humans.

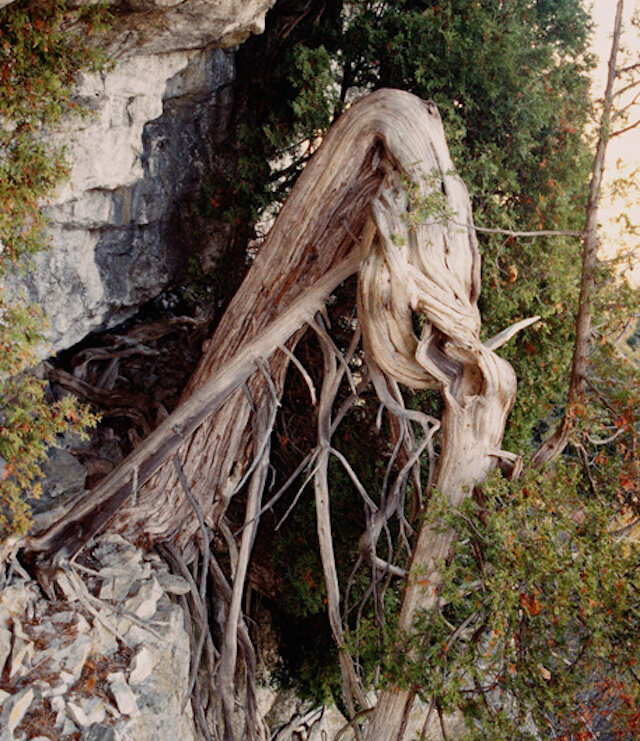

Growing out of these cliffs are small, gnarled cedar trees. It wasn’t until Larson had been working there for three years when he discovered something unexpectedly remarkable: these little trees were hundreds of years old. This was much older than Larson thought they were.

“They were overtly struggling to survive, but we thought the struggle was 60 years old, not 600 years old,” he said on Atlas Obscura [1].

Larson first made the discovery back in 1988 when he was working on the outskirts of Toronto. He was counting the rings of a tree under a microscope and found there to be hundreds. At first, he thought that he must be wrong, or that there must be some other explanation. There was no way that an old-growth forest like that could exist so close to a major city.

The tree ring lab at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, however, confirmed Larson’s initial analysis: the forest was hundreds of years old. In fact, some of the forest’s oldest trees were approximately seven hundred years old.

Read: Ancient Forestry Technique Produces Lumber Without Cutting Down Trees

What is an “Old Growth Forest”?

This secret forest, at one time, would not have been so secret. In fact, at one point Southern Ontario would have been covered with oak trees that were hundreds of years old. As people moved into the area, however, they cut many of these trees down for lumber, or to make room for farmland.

While there are many areas in North America with thick forests, most of these are very young trees, relatively speaking. That brings us to the question- what makes a forest an “old growth forest”?

That question is more difficult to answer than you might initially think. This is because there is no universally-accepted definition of an old-growth forest.

In the 1970s, scientists used the term “old growth” for forests that were at least 150 years old. These forests also had to be highly complex with a significant amount of biodiversity. Environmentalists, however, used the term to describe any forest with large, old trees that had been relatively untouched by humans. Under this definition, many more forests qualify as “old growth”.

Tom Spies is an emeritus scientist with the U.S. Forest Service research division and professor at Oregon State University’s College of Forestry. He says that the definition can change based on the agenda of the person trying to define it.

“If you approach the issue with a particular agenda,” he said, “you can take a really narrow definition that would exclude a lot of forest from being defined as old growth. Or you can have a very broad definition which would capture a lot of forest conditions.” [2]

The lack of definition, unfortunately, has presented problems when it comes to conserving and protecting forests.

Multiple Definitions

In his book, Eastern Old-Growth Forests: Prospects for Rediscovery and Recovery, Robert Leverett summarized the many ways that scientists have attempted to define old-growth forests:

Definitions that emphasize lack of disturbance by humans (at least post-colonization); there are abundant old trees some of which are approaching the maximum old-age for the species.

Definitions that use a minimum age (typically around 150 years) combined with presence of old-growth characteristics such as logs, snags (standing dead trees), canopy gaps etc.; some human disturbance may be permitted.

Definitions that emphasize stand development, in particular climax forest – that is, the forest is in a stable state where trees are dying of old age and being replaced, and may continue to be stable for centuries.

Definitions that use an economic threshold. Old-growth stands are past the economic optimum for harvesting – usually between 80-150 years, depending on the species [3].

Again, this definition really depends on who is defining it. Brad Kahn, a spokesperson for the Forest Stewardship Council, says it all comes down to a judgement call.

“If you ask Greenpeace, it’s going to be a different answer than a timber company,” he explained [2].

Is this “Secret Forest” Protected?

The trees in this “secret forest” on the Niagara escarpment are not formally protected in any way. Despite the fact that they live in areas with significant human populations, however, their dwelling offers them protection instead. Situated high up on steep cliffs, they have been safe from people for centuries.

Most of these trees are Eastern White Cedars, and the Niagara Escarpment has acted as a refuge for them for their entire existence. It’s a challenging environment in which to live, but there are very few predators, no fire, no floods, and very little competition.

“There is something wonderful about animals and plants that depend on cliffs,” says Larson. “They’re there because no one else can live there. They have a physiological toughness that allows them to sit out in these places that nothing else can touch, and they thrive there.” [1]

But how have these trees survived for so long in such hostile conditions? It comes down to how they use their roots. For most trees, their roots feed the entire tree. That means that if one part of the root system sustains damage or dies, the entire tree suffers.

Cedars, on the other hand, connect different parts of their root system to certain parts of the tree. This way, if one section of roots dies, only the part of the tree dies. The rest will live on.

This is particularly important for the trees living on the cliffs of the Niagara escarpment. If one part of their root system loses access to water or is damaged, the rest of the tree just keeps growing. This means that one side of a tree might show ten years of growth, while the other side has been growing for a thousand years [1].

The Future of the Forest

Just because this area has remained a “secret forest” for so long, however, does not mean that they are impervious to change. Peter Kelly, who worked with Larson to study the trees and the cliffs for 20 years, says that when it comes to trees, you always have to be worried. Bugs or blight can wipe out entire forests, and climate change can still impact the trees. It is impossible to know if trees will continue to thrive in these changing conditions.

Currently, however, Larson says this secret forest appears to be thriving. These small, gnarly trees just keep bouncing back. Hopefully, they will continue to do so for many more years.

Keep Reading: Artist Creates Giant Wood Sculptures and Hides Them in Copenhagen Forests