A new cancer treatment is on the horizon: a laser beam device that can detect and kills cancer cells circulating in our blood on the spot.

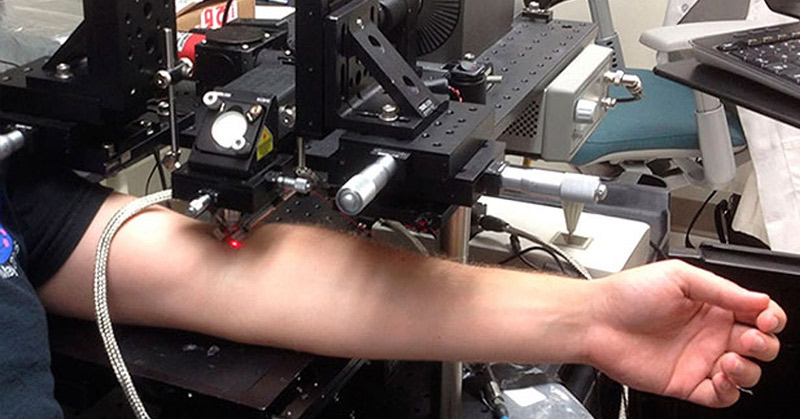

In a study published by Science Translational Medicine, researchers developed technology able to track cancer cells with more precision than conventional methods. They beamed lasers onto the skin of the patient and found cancer cells using heat and sound waves.

Most conventional methods of detecting cancer are limited when it comes to diagnosing cancer in its early—and most treatable—stages.

This system is 1,000 times more sensitive than similar systems, accurately detecting tumor cells 27 times out of 28 in cancer patients. Not only that, the researchers were able to kill a high percentage of these cells.

With further research and development, this system could be the future of cancer treatment. It promises a thorough yet noninvasive method of discovering and killing cancer cells before they spread and create further tumors into the body.

“This technology has the potential to significantly inhibit metastasis progression,” says Vladimir Zharov, the lead researcher, and director of the nanomedicine center at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. [1]

What Causes Cancer?

Cancer is a broad term for a collection of diseases where cells divide and spread into surrounding tissues. This spread can begin from anywhere in the body. [2]

Healthy cells die when they become damaged or old, and new cells replace them. Cancer cells linger despite being old, damaged, and abnormal. Therefore, the new cells become unneeded, and without a proper function in the body, they keep dividing, which creates a tumor.

These tumor cells spread by: [2]

- Invading nearby tissue, and

- Floating into the bloodstream or lymph system, and creating a new tumor in the body far from the original one.

The spread from the original tumor to vital organs can cause fatality.

These cancer cells ignore signals that tell cells to stop die or dividing, a natural function the body uses to prevent unneeded cells.

Cancer is a genetic disease, in that it changes our genes and affects how they function. [2] While we can have inherited genes that can increase our cancer risk, it can also come from damage to a person’s DNA from their environments, such as tobacco smoke and ultraviolet rays from the sun. [2]

How the Laser Cancer Detector Works

Zharov and his team tested their technology on patients with melanoma (skin cancer).

The researchers positioned the laser at a vein and sent energy into the bloodstream. This creates heat causing the circulating cancer cells to expand. Circulating melanoma cancer cells absorb more of this light energy than healthy cells. This heated expansion creates sound waves detected and recorded by an ultrasound device placed over the skin next to the laser beam. These ultrasound recordings reveal the location of cancer cells passing through the bloodstream. [1]

Being able to create these soundwaves is known as the photoacoustic effect, which was first discovered by Alexander Graham Bell in 1880. He transmitted sound waves through his invention, the photophone and first ever telephone. In homage to him, Zharov’s team nicknamed their invention the “cytophone,” cyto- meaning ‘of cell.’ [3]

This laser can also destroy cancer cells. The heat causes vapor bubbles to gather around the tumor cells. The bubbles expand then collapse, much like blowing up and popping a soap bubble. This can kill the cancer cell beneath it. [1]

The “Cytophone” and Other Cancer Cell Detection Systems

Zharov was inspired to create this system ten years ago. He tested and refined his theory on animals and eventually demonstrated it to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). With their approval, he was able to begin the clinical trial—the first-ever noninvasive cancer cell treatment method tested on humans.

Other methods of detecting spreading tumor cells have been tried before. These methods usually involved drawing blood and analyzing the blood cells outside of the body. The most developed two are:

1. CellSearch

One of these devices, called CellSearch, was approved by the FDA. It can test small samples of blood drawn out of the body. In standard cancer care and diagnostic, this tactic is not commonly used. [4]

2. Wearable Device from the University of Michigan

Similar technology progressed farther than Cell Search. Researchers at the University of Michigan created devices worn on the wrist that pump blood out of the body, filter the cancer cells, and release clean blood back into the veins. This technology was tested on dogs and it pumped several tablespoons of blood through the device in two to three hours. [5]

The wrist device pales in comparison to Zharov’s, which can test a liter of blood within one hour. Zharov’s also surpasses CellSearch with the laser’s advanced precision of tracking cancer cells. Best of all, the blood remains in the body the whole time.

The Future for the “Cytophone” and Cancer Research

“In one patient, we destroyed 96 percent of the tumor cells [under the laser beam,]” says Zharov. [1] He and his team hope the laser will be even more effective when they increase the heat sent into the bloodstream.

For their next project, Zharov and his team plan to test this device on a large group of participants undergoing conventional cancer therapy. The team will test the effects of this combined treatment on the spreading of cancer cells. They also hope to expand the technology to find other circulating cancer cells other than melanoma.

Future studies will report these findings.

Sources

- In vivo liquid biopsy using Cytophone platform for photoacoustic detection of circulating tumor cells in patients with melanoma https://stm.sciencemag.org/content/11/496/eaat5857

- What Is Cancer? https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer

- Alexander Graham Bell and the Photoacoustic Effect in 1880 https://fys.kuleuven.be/zmb/Research_themes/rt_photoacoustic/rt_photo_pha

- CellSearch https://www.cellsearchctc.com/

- A temporary indwelling intravascular aphaeretic system for in vivo enrichment of circulating tumor cells https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-09439-9